Fundadores e Inversores

Las startups suelen funcionar con un déficit al diseñar y construir el producto. Pero las empresas están diseñadas para ganar dinero y, con el tiempo, a medida que mejoran la economía de la unidad y los costos de adquisición de clientes, es probable que se solvente.

Como mínimo, eso es a lo que apostarán sus inversores. Eso significa que la diapositiva de su modelo de negocio debe pintar una imagen que muestre dónde se encuentra ahora y cómo puede crecer el negocio con el tiempo.

En teoría, su “modelo de negocio” podría incluir todos los aspectos del negocio; el Business Model Canvas es una forma de explorarlo, y fácilmente podría pasar una hora simplemente hablando sobre todo el modelo comercial de extremo a extremo. Sin embargo, a los efectos de un argumento de financiación, es probable que solo necesite algunos elementos cruciales:

- COGS, o Coste de los Bienes Vendidos, es el costo incremental por cada unidad que entrega. Para el software, esto normalmente se redondea a cero, pero para productos de hardware o negocios más orientados a servicios, el costo unitario puede ser sustancial.

- CAC, o Coste de Adquisición de Clientes, es el costo de ventas y marketing dividido por la cantidad de clientes que ha registrado.

- LTV, o Valor durante la Vida del Cliente: ¿Cuánto vale cada cliente, en promedio, una vez que los registra?

- Coste de I + D es lo que cuesta desarrollar el producto. Por lo general, esto no se incluye en el modelo comercial, pero si el costo de I + D es astronómico y la línea de costo a beneficio nunca se cruza, podría tener un problema que vale la pena explorar.

- El Modelo de Precios no suele ser parte del modelo de negocio en sí (se incluye en LTV), pero si está haciendo algo inusual o creativo con su precio, vale la pena incluirlo, ya sea aquí o en su diapositiva de lanzamiento al mercado.

Desglosar esos números y presentarlos de la manera correcta puede beneficiar enormemente la forma en que cuentas la historia de tu startup a los inversores.

Costo de Adquisición de Clientes

Cualquiera que sea su estrategia para atraer clientes a través del embudo de adquisición, probablemente cueste dinero. Algunas empresas se anuncian directamente, algunas se anuncian a través de personas influyentes, otras van a ferias comerciales. Hay muchas formas de encontrar nuevos clientes; algunos canales serán más caros y, si tiene suerte, algunos incluso pueden ser gratuitos.

Como empresa, es importante tener una idea clara de cuáles son todos sus canales de adquisición y cuánto cuestan. Me referiré a esto más abajo, pero para que una diapositiva de modelo de negocio tenga sentido, probablemente necesite informar del CAC combinado.

Una nota rápida aquí: «Nuestro crecimiento es orgánico» o «No hemos gastado un centavo en marketing» no es lo que los inversores quieren escuchar. Sí, es impresionante, pero esos canales de clientes no se pueden escalar rápidamente, y si de repente se encuentra con un presupuesto de marketing de $30,000 por mes, no sabrá dónde desplegar efectivo para crecer más rápido.

Valor durante la Vida del Cliente (Lifetime Value)

Si realiza ventas únicas, su valor de por vida es el valor de la venta. Eso se aplica a cosas como los televisores: las personas compran un televisor y no necesitan otro durante al menos otra década.

Pero incluso las compras únicas y raras pueden tener un LTV sorprendentemente alto si puede construir una relación. Si usted es un vendedor de automóviles que vende un automóvil nuevo, podría, por ejemplo, agregar contratos de servicio, lo que alentaría a los clientes a regresar.

Para los negocios de suscripción y SaaS, LTV está claro: ¿cuánto tiempo puede retener a los clientes y cuál es su gasto promedio? ¿Puedes venderles más o de forma cruzada, lo que aumentaría el LTV?

La única vez que conoce el valor real de la vida de un cliente es cuando deja de ser un cliente. Para algunas empresas, que un cliente termine la relación contigo es algo positivo; un buen ejemplo de esto sería un sitio de citas, donde el éxito se mide por cuántas personas no regresan porque se establecieron en relaciones felices.

Pero que un cliente termine una relación contigo es algo que normalmente deseas evitar. Entonces, para calcular el valor de por vida de un cliente, debe hacer una suposición calculada sobre cuánto tiempo permanecerá cada cliente y cuáles son sus patrones de gasto. Al comienzo del viaje de una startup, esto será poco más que conjeturas calificadas. Pero a medida que el negocio crezca, comenzará a notar patrones y hábitos de los clientes que podrían facilitar la creación de modelos más sofisticados que obtengan una mejor aproximación al LTV.

Esto puede ser obvio, pero vale la pena mencionarlo: si su LTV es más bajo que su CAC, tiene un problema grave. Lo mismo es cierto si los números coinciden más o menos; si no está obteniendo una ganancia por cliente, eventualmente se quedará sin efectivo porque la I+D y las operaciones del negocio seguirán incurriendo en costos.

Su relación CAC a LTV es importante para los inversores. Si sus clientes gastan $ 10 por cada $ 1 que gasta en adquirirlos, debe gastar tanto dinero como pueda para adquirir tantos clientes como pueda.

Algunas empresas optan por no informar su LTV porque se sienten incómodas tratando de modelar el comportamiento de los clientes durante cinco o seis años. En cambio, intentan informar el gasto promedio del primer año y asegurarse de que el costo de adquisición de clientes esté cubierto en ese primer año. La suposición es que si logra mantener a su cliente más allá del primer año, es esencialmente una ganancia pura.

Coste de los Bienes Vendidos (COGS)

Los COGS pueden variar enormemente de una empresa a otra, según el mercado y la industria. La entrega de un producto puramente de software como servicio a menudo se puede hacer de manera muy económica, y el COGS se redondea a cero. Para otros productos que hacen un uso más intensivo del servidor (por ejemplo, si tiene que ejecutar modelos de IA complejos que consumen mucha potencia de procesamiento, o si tiene que transcodificar y enviar grandes volúmenes de contenido de video), el costo de entrega puede ser significativamente mayor.

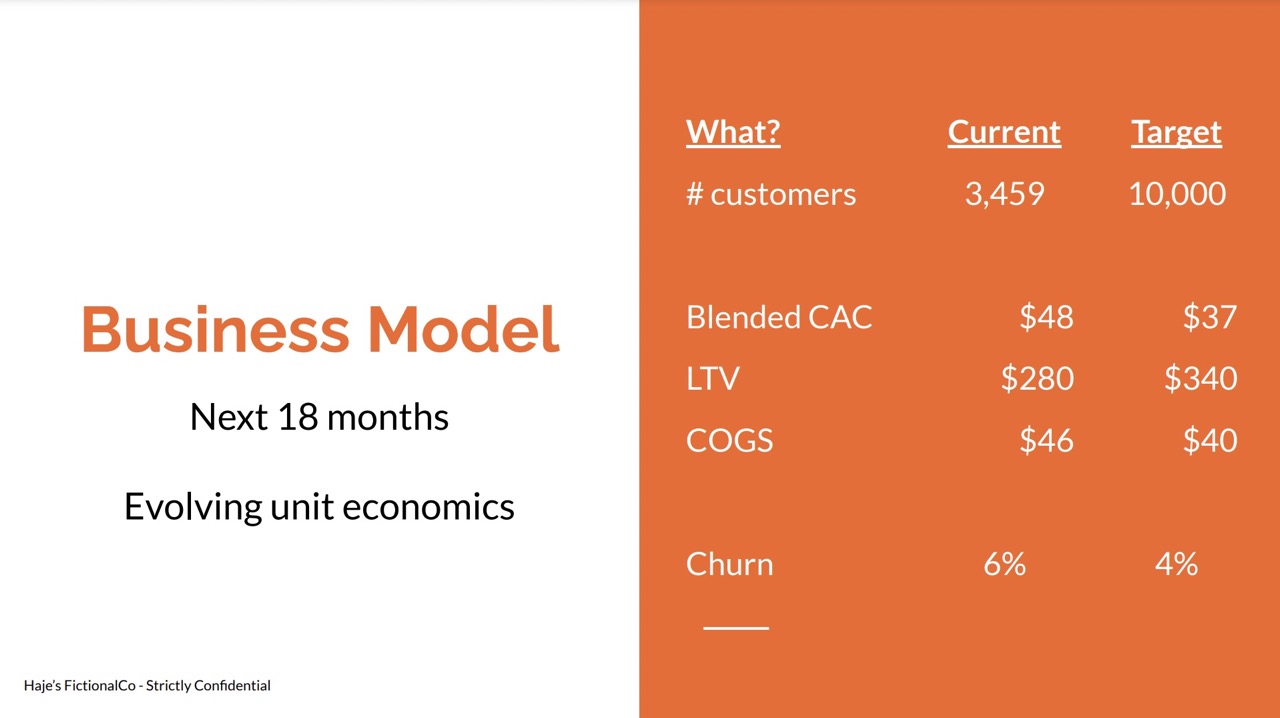

Una forma de presentar el modelo de negocio es mostrar una instantánea de lo que es cierto actualmente en el negocio, así como también las cifras hacia las que está trabajando. Puede profundizar en esto en la sección del plan operativo, pero es útil poder hablar sobre objetivos específicos y cómo planea llegar allí.

Es difícil dar un consejo generalizado sobre cómo tratar el COGS como parte de un lanzamiento, pero como regla general, si su COGS es menos del 10 % de sus ingresos, probablemente pueda ignorarlo como parte del lanzamiento. Si sus márgenes de contribución son relativamente escasos, querrá incluir COGS como parte de la conversación porque probablemente le dará prioridad a reducir el costo de entrega de su producto o servicio.

Investigación y Desarrollo

La investigación y el desarrollo a menudo tienen un coste significativo, pero por el bien de esta diapositiva en particular, ignórela. El modelo de negocio de una empresa, en el contexto de un argumento de financiación, se trata en gran medida del costo y los ingresos por cliente, y posiblemente de la economía de la unidad.

La I+D suele ser una parte diferente de la historia de una startup; se desglosa de manera diferente y la mayoría de las empresas no amortizan su I+D como parte de la economía de su unidad. Sus costos de investigación y desarrollo aparecerán en su plan operativo, así que no caiga en la tentación de confundir la historia en este punto.

Modelo de Precios

Su modelo de precios es cómo cobra a sus clientes. Si está vendiendo hardware, a menudo es el costo del widget, más potencialmente un modelo de suscripción para cualquier software que lo utilice. Si está creando un negocio SaaS, probablemente tendrá un modelo de precios por negocio o por usuario, y posiblemente diferentes niveles, según las necesidades del cliente. Otras empresas pueden tener tarifas de registro, contratos de servicio, anticipos, costos de instalación o cualquier cantidad de formas de pago.

Para muchas empresas en su etapa inicial, el modelo de fijación de precios es bastante sencillo, y de hecho debería serlo; es poco probable que su principal contribución al mercado sea la innovación en modelos de precios complicados. A medida que el negocio crezca y la base de clientes evolucione, tendría sentido cobrar más por las características que desbloquean un mayor valor para ciertos segmentos de clientes.

Para su plataforma de lanzamiento, la regla es simple: incluya un modelo de precios si realmente cree que necesita una explicación.

Todo en conjunto

Como parte de diversos de Pitch Deck y documentación online, existen una gran cantidad de excelentes ejemplos de modelos comerciales. Aquí están algunos:

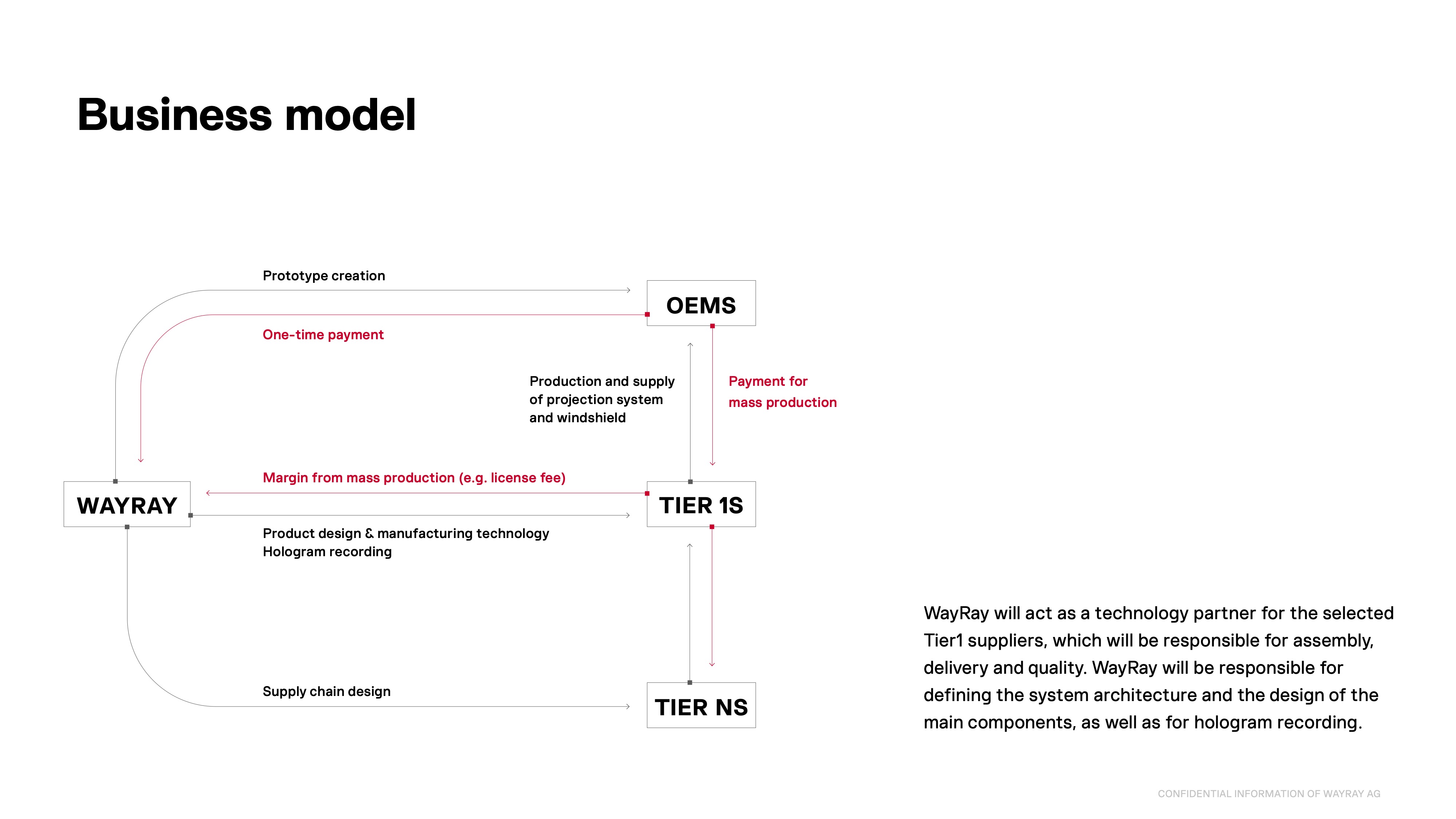

WayRay presentaba 75 diapositivas muy complicada que entraba en muchos detalles en su Serie C de $80 millones. El modelo comercial de la compañía es lo suficientemente complejo como para justificar una explicación más detallada. Hubiera sido adecuado cuentificar la cantidad de dinero que fluye para la producción en masa, los pagos de un solo tipo y las tarifas de licencia, pero tener una diapositiva explicativa es útil en este caso.

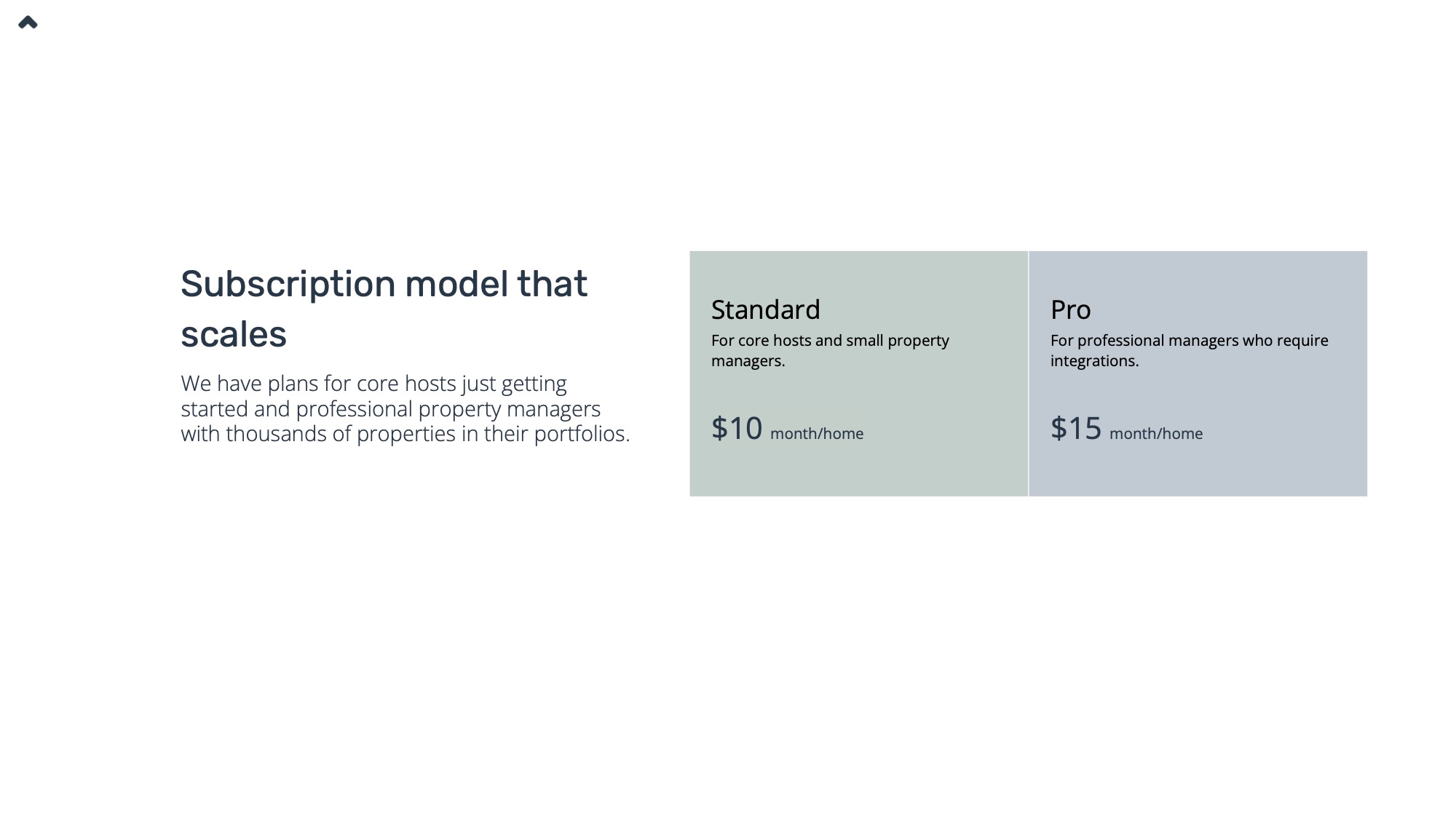

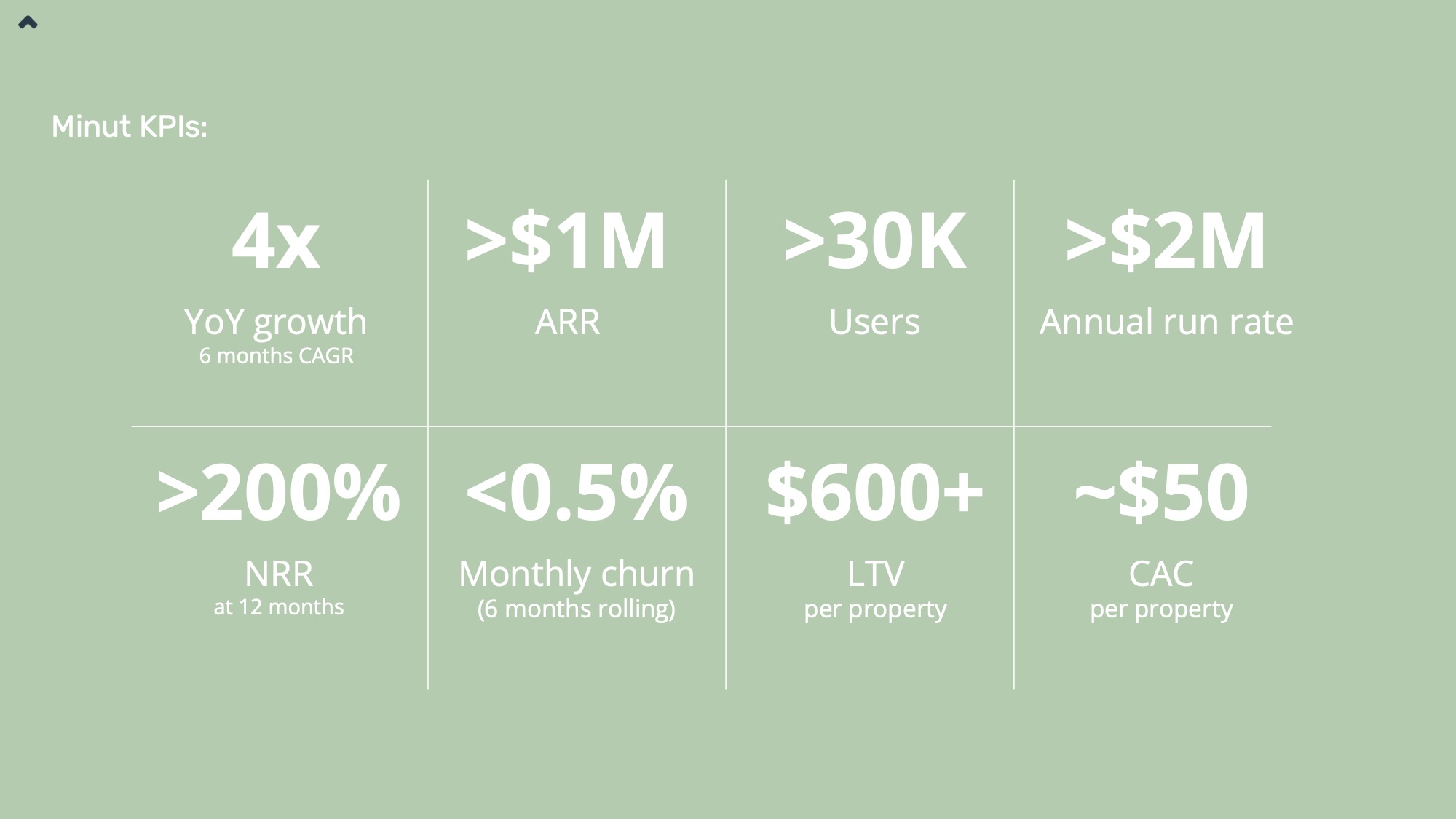

Para su Serie B de $ 15 millones, Minut muestra un modelo de precios mucho más simple: suscripciones con dos niveles. Eso es todo, sin lujos, sin confusión. Frente a presentar más detalles , la empresa optó por incluir algunos de los datos importantes de su modelo de negocio en la sección de KPI:

La sección de KPIs de Minut incluye el CAC y LTV.

Mostrar la rotación, LTV y CAC en los KPI ayuda a formar una imagen más completa del Modelo de Negocio con el que opera Minut, lo que les funcionó muy bien en este caso.

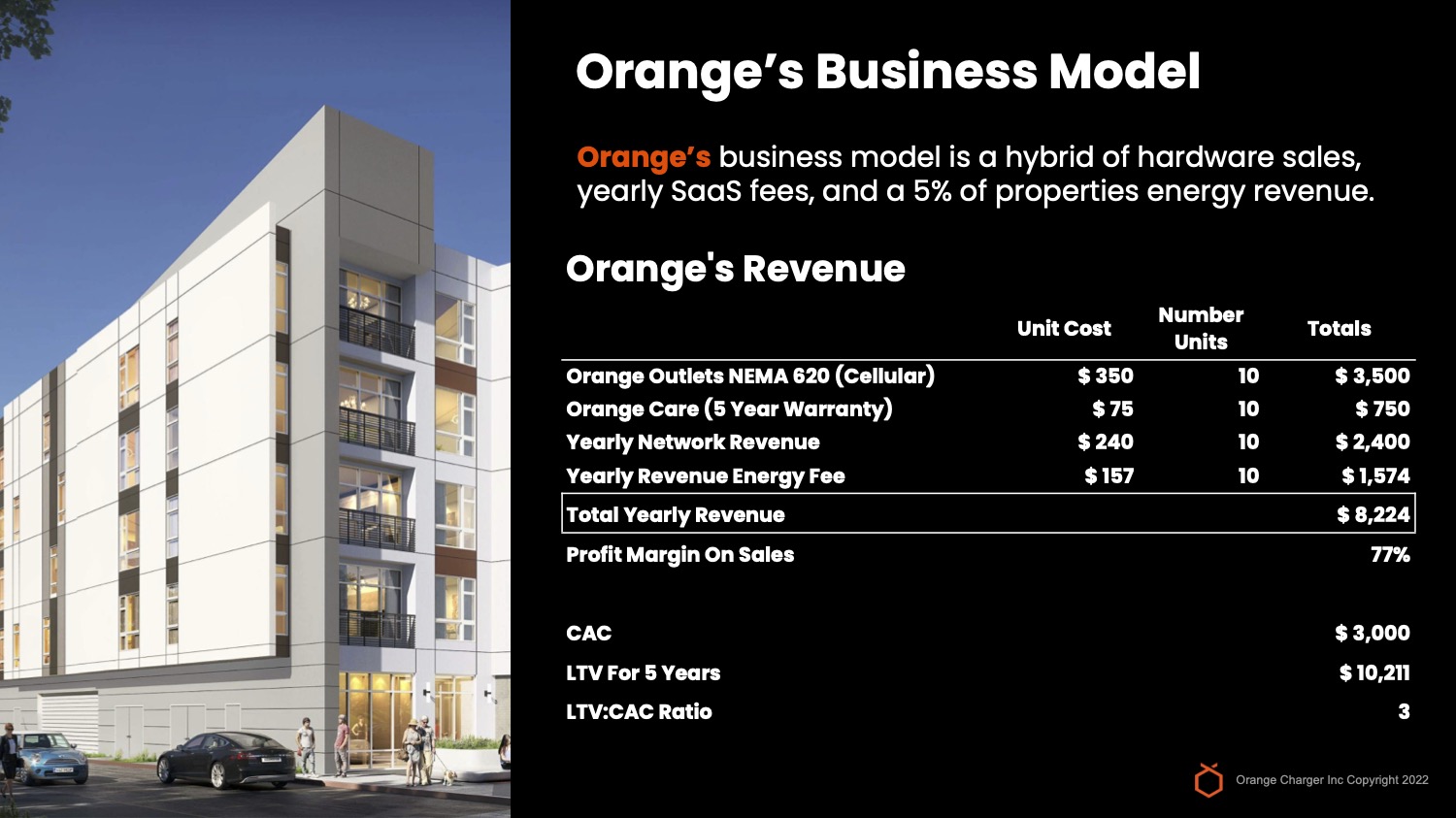

Finalmente, una de las mejores presentaciones incluye las siguientes diapositivas de Modelos de Negocios. Su origen, Orange:

La diapositiva del Modelo de Negocio de Orange es casi perfecta. Muestra todos los datos importantes que un inversor necesita para obtener una comprensión completa de la dinámica del Modelo de Negocio de la empresa: costes unitarios, CAC, LTV y relación CAC:LTV.